When you pick up a prescription, you might not realize you’re making a choice that could cost you $80 or $8. It’s not about which drug works better-it’s about what your insurance lets you pay for. Most people assume generics and brand-name drugs are the same. And technically, they are. But when it comes to insurance coverage, the rules couldn’t be more different.

Why Insurance Favors Generics

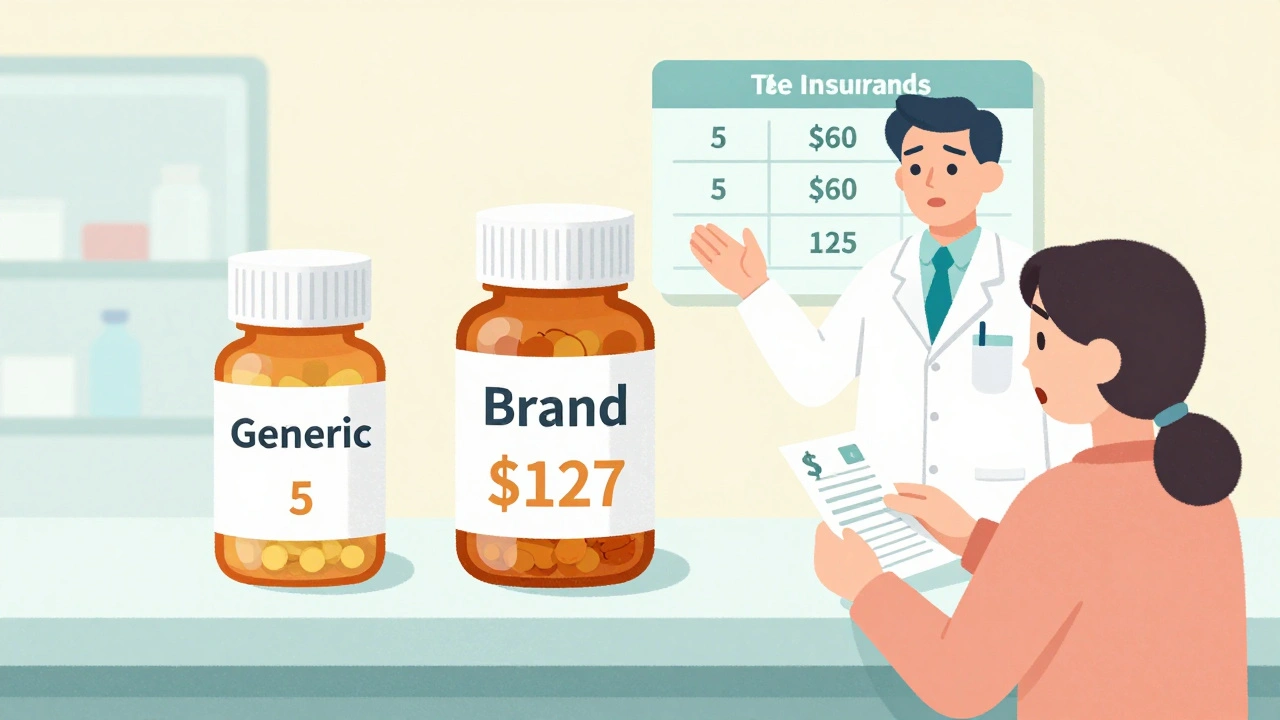

Generic drugs aren’t cheaper because they’re lower quality. They’re cheaper because they don’t need to pay for research, marketing, or patent protection. The FDA requires them to have the same active ingredient, strength, dosage form, and effect as the brand. That’s not a suggestion-it’s the law. But insurance companies treat them like a completely different product. Most plans use a tiered system. Tier 1 is for generics. You pay $5 to $15 for a 30-day supply. Tier 2 or 3? That’s where brand-name drugs live. Copays jump to $40, $60, even $100. Some plans don’t even charge a flat fee-they charge you a percentage of the drug’s total cost. For a $500 brand-name pill, that could mean $125 out of pocket. Here’s the kicker: if a generic exists and you choose the brand, you don’t just pay the brand’s copay. You pay the generic copay plus the full price difference. So if the brand costs $120 and the generic is $8, you pay $15 (generic copay) + $112 (the rest) = $127. That’s not a mistake. It’s policy.How Substitution Works (And When It Doesn’t)

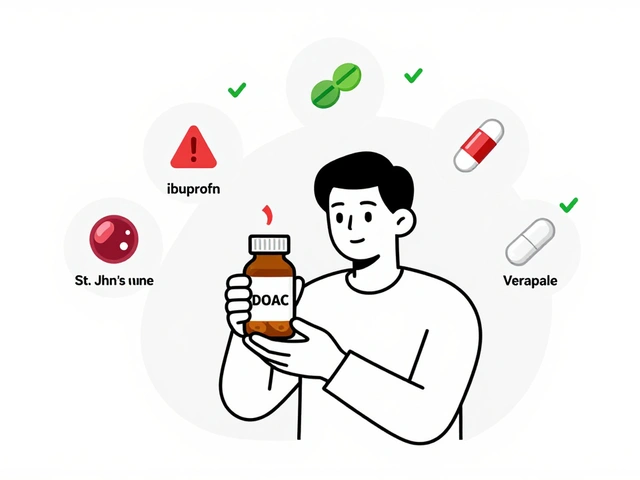

Pharmacists are legally allowed to swap a brand-name drug for a generic unless the doctor writes “dispense as written” or “do not substitute.” Every state allows this. But the rules vary. In some places, the pharmacist must tell you. In others, they just do it. The problem? Not all generics are created equal-even if they have the same active ingredient. Inactive ingredients like fillers, dyes, or coatings can cause side effects in sensitive patients. That’s why people on thyroid meds like levothyroxine, epilepsy drugs like phenytoin, or blood thinners like warfarin often report problems after switching. Twenty-seven states have special rules for these “narrow therapeutic index” drugs. Some require the doctor to justify why the brand is needed. Others let the pharmacist know upfront: “Don’t substitute.” Medicare Part D, which covers most seniors, requires substitution unless medically necessary. In 2022, 91% of Part D prescriptions were generics. But that doesn’t mean everyone’s happy. A 2022 CMS survey found only 63% of Medicare users were satisfied when forced to switch from a brand they’d been on for years.What Gets in the Way: Prior Authorization and Step Therapy

Insurance doesn’t just make generics cheaper-they make brands harder to get. Two big tools: prior authorization and step therapy. Prior authorization means your doctor has to jump through hoops before the insurer will pay for the brand. For brand-name drugs, 22.7% require this. For generics? Just 2.1%. The average wait time for approval? 3.2 business days. And 41% of those requests need a follow-up call from the doctor. Step therapy is even more frustrating. It means you have to try the generic first-even if your doctor says it won’t work for you. For 35.6% of specialty medications, you must fail one or two generics before you can get the brand. That can mean weeks of ineffective treatment, worsening symptoms, or emergency visits. To get an exception, you usually need three documented failed attempts with generics. That’s not just paperwork-it’s time. And time is health.

Medicaid, Medicare, and Commercial Plans: Who Gets What

Not all insurance is the same. Medicaid pays the lowest price available for generics thanks to federal “best price” rules. That means Medicaid reimburses pharmacies 87% less for generics than for brand-name drugs. It’s not about savings-it’s about survival. Medicare Part D has its own twist. After you hit the coverage gap (the “donut hole”), you pay 25% of the drug’s cost-same for generics and brands. But because generics are cheaper to start with, you’re still paying less overall. Commercial plans? They’re the most confusing. A 2022 IQVIA survey found average copays for generics were $11.85. For brand-name drugs? $62.34. That’s more than five times as much. And many plans don’t clearly explain the difference until you’re at the pharmacy counter.Why People Still Choose Brands-Even When It Costs More

You’d think everyone would go for the generic. But they don’t. Why? Some patients have real reactions. On forums like Reddit and Drugs.com, thousands share stories: “My anxiety got worse after switching to generic Wellbutrin.” “I had seizures when they changed my Lamictal.” “I couldn’t sleep for weeks after my thyroid med was swapped.” A 2022 JAMA Neurology study found 12.3% higher seizure rates in epilepsy patients switched from brand to generic. That’s not a fluke. It’s a pattern. Doctors notice it too. Dr. Aaron Kesselheim from Brigham and Women’s Hospital found that 68% of physicians have patients who report side effects with generics-even though the active ingredient is identical. That’s not just placebo. It’s biology. And insurance policies don’t always account for it. Then there’s the money factor. Brand manufacturers offer copay cards that cut out-of-pocket costs to $0 or $10. But you can’t use those if you’re on Medicare or Medicaid. So if you’re a senior or on public insurance, you’re stuck paying the full difference.What’s Changing in 2025 and Beyond

The rules are shifting. The FDA’s new GDUFA III rules, starting in 2025, will require clearer labeling on generics to show their therapeutic equivalence rating. That means pharmacies and insurers will have to be more transparent about whether a generic is truly interchangeable. Medicare is also stepping in. The 2024 proposed rule wants to cut prior authorization wait times for brand-name drugs to 72 hours-down from the current range of same-day to 14 days. That’s a big deal for patients waiting for relief. Meanwhile, “authorized generics”-the brand-name company’s own generic version-are now 46% of all generic prescriptions. These often get better coverage than third-party generics because insurers see them as more reliable. And let’s not forget the Inflation Reduction Act. It caps insulin at $35 a month and puts a $2,000 annual out-of-pocket cap on all drugs for Medicare users. That’s helping people on expensive brands-but it’s also pushing insurers to find cheaper alternatives faster.

What You Can Do

You don’t have to accept whatever your plan gives you.- Ask your pharmacist: “Is there a generic? What’s the cost difference?”

- Check GoodRx or SingleCare before you pay. Sometimes the cash price is lower than your copay.

- If you’ve had problems with a generic, ask your doctor to write “dispense as written” on the prescription.

- If your plan denies coverage, file an appeal. You have the right. Keep records of side effects, doctor notes, and pharmacy receipts.

- For Medicare users: Use the Plan Finder tool. Not all plans treat generics the same.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are generic drugs really the same as brand-name drugs?

Yes, by FDA standards. Generics must contain the same active ingredient, strength, dosage form, and work the same way in the body. But inactive ingredients like fillers or dyes can vary, and some people report side effects or reduced effectiveness after switching-especially with thyroid, epilepsy, or blood thinner medications.

Why do I pay more if I choose a brand-name drug when a generic is available?

Insurance plans use a cost-sharing rule called “brand penalty.” You pay your generic copay (say $10) plus the full price difference between the brand and generic. So if the brand costs $100 and the generic is $8, you pay $10 + $92 = $102. It’s designed to push you toward the cheaper option.

Can my doctor stop the pharmacy from substituting a generic?

Yes. Your doctor can write “dispense as written” or “do not substitute” on the prescription. This is legal in all 50 states. Some states require additional documentation, especially for drugs like levothyroxine or warfarin, where small changes can have big effects.

Why do some people have bad reactions to generics?

The active ingredient is identical, but inactive ingredients-like dyes, binders, or coatings-can differ. For people with sensitivities, these can cause stomach upset, headaches, or changes in how the drug is absorbed. This is especially common with thyroid medications, antidepressants, and seizure drugs. Studies show a small but significant number of patients experience therapeutic failure after switching.

What’s the difference between a generic and an authorized generic?

An authorized generic is made by the original brand-name company but sold under a generic label. It’s chemically identical to the brand, often with the same inactive ingredients. Insurance plans often cover these more favorably than third-party generics because they’re seen as more reliable. About 46% of all generic prescriptions in the U.S. are authorized generics.

Can I get financial help for brand-name drugs if I’m on Medicare?

No. Brand manufacturers can’t offer copay cards to Medicare or Medicaid patients due to federal anti-kickback laws. But Medicare’s Inflation Reduction Act caps out-of-pocket drug costs at $2,000 per year starting in 2025, which helps people on expensive medications. You can also apply for patient assistance programs directly through drugmakers.

How do I know if my insurance plan is forcing me to switch to a generic?

Check your plan’s formulary online or call customer service. Look for terms like “preferred,” “non-preferred,” or “step therapy.” If your doctor prescribes a brand and your pharmacy says it’s not covered unless you try a generic first, that’s step therapy. You have the right to appeal that decision.

What’s the best way to fight an insurance denial for a brand-name drug?

Start with your doctor. They need to submit a letter of medical necessity, including your history of side effects or failed trials with generics. Include lab results, dosage records, and pharmacy logs. If denied, file a formal appeal with your insurer. You have 180 days. If that fails, you can request an external review. Many appeals succeed when backed by clinical evidence.

Taya Rtichsheva

December 9, 2025 AT 03:30So basically insurance wants you to suffer a little longer so they can save a buck

Christian Landry

December 10, 2025 AT 16:50bro i switched to generic adderall and felt like a zombie for 3 weeks 😩 turned back and my brain came back. why do they make this so hard?

Maria Elisha

December 11, 2025 AT 14:14my pharmacist just swaps it without telling me. i found out i was on a different generic when my anxiety spiked. no one cares.

Mona Schmidt

December 12, 2025 AT 15:36The distinction between active and inactive ingredients is critical here. While the FDA mandates bioequivalence for active components, the variability in excipients-such as lactose, dyes, or binding agents-can significantly alter dissolution rates and gastrointestinal absorption, particularly for drugs with narrow therapeutic indices. This is not anecdotal; peer-reviewed studies in the Journal of Clinical Pharmacology have demonstrated measurable pharmacokinetic differences in patients with comorbid gastrointestinal conditions. Insurance policies that treat all generics as interchangeable ignore these biological nuances, effectively prioritizing cost over individualized care.

Courtney Black

December 14, 2025 AT 13:44It’s not about the drug. It’s about the system. The system doesn’t care if you sleep. It doesn’t care if you seizure. It doesn’t care if you cry in the pharmacy parking lot because you can’t afford the brand your body actually tolerates. It cares about spreadsheets. It cares about quarterly reports. It cares about the bottom line. And when your life becomes a line item in a corporate dashboard, you’re not a patient-you’re a cost center. And cost centers get optimized. Out. Of. Existence.

iswarya bala

December 15, 2025 AT 22:00in india we dont even have this problem so much, generics are trusted and cheap. but i know ppl in usa suffer a lot. hope things get better soon 🙏

Katie Harrison

December 17, 2025 AT 21:43I’ve been on levothyroxine for 12 years. Switched to a generic in 2021. My TSH went from 1.8 to 8.4. My doctor had to write ‘dispense as written’ twice before the pharmacy stopped swapping it. I’m not ‘overreacting.’ I’m surviving. And now I have to carry my prescription like a legal document just to get the same pill I’ve taken since 2012. This isn’t healthcare. It’s bureaucratic harassment.

Guylaine Lapointe

December 17, 2025 AT 21:44Wow. So the government lets insurance companies play Russian roulette with people’s health because it’s cheaper? And then they act like it’s our fault for not ‘doing our research’? You know what? I’m done being polite about this. This isn’t a ‘cost-saving measure.’ It’s a public health crisis disguised as policy. People are dying because they can’t afford the version of their drug their body actually works with. And the people in charge? They’re sipping lattes in D.C. while we’re Googling ‘can you die from bad generic seizure meds’ at 2 a.m. Shameful.