When your liver fails, there’s no backup. No second chance. No pill that can replace what it does-filtering toxins, making proteins, storing energy, regulating blood sugar. For people with end-stage liver disease, a transplant isn’t just an option-it’s the only way to survive. But getting one isn’t as simple as signing up. It’s a long, strict, and deeply personal journey that begins long before the operating room.

Who Gets a Liver Transplant?

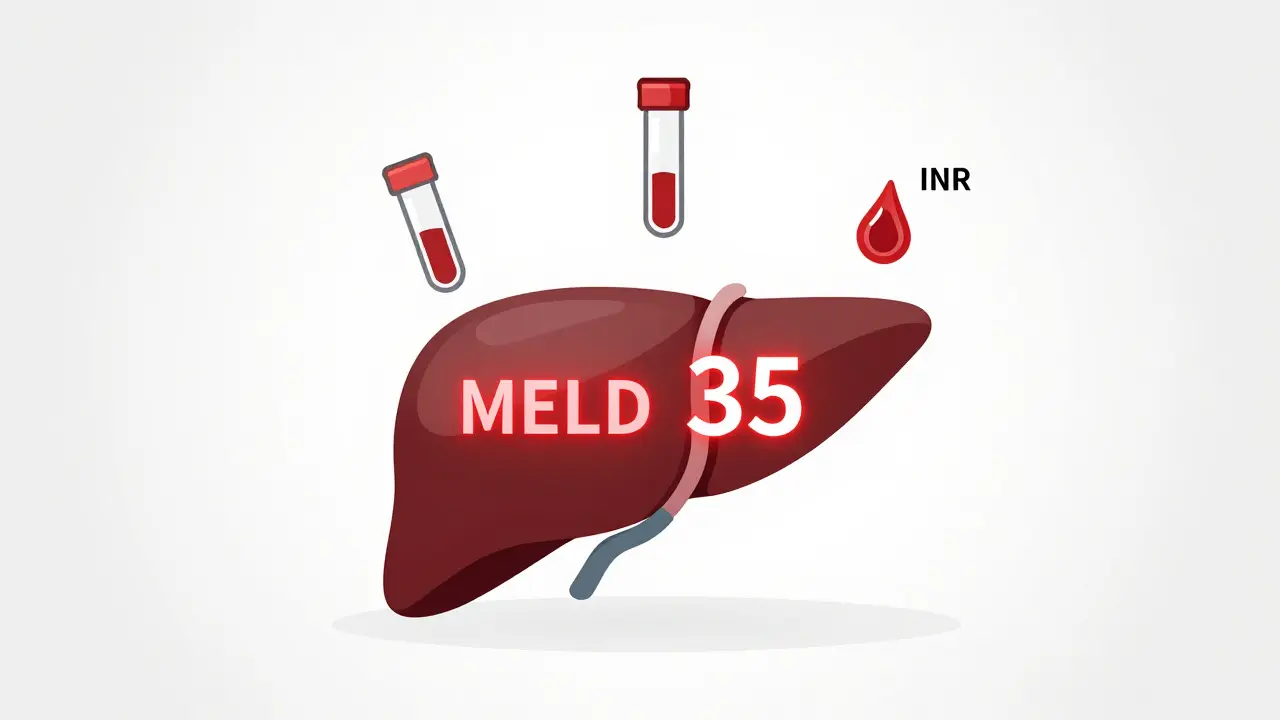

Not everyone with liver disease qualifies. The system is designed to give the organ to those who need it most and have the best chance of surviving. The Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score is the key. It’s calculated using three blood tests: bilirubin, creatinine, and INR. The higher the score, the sicker you are. Scores range from 6 to 40. Someone with a MELD of 35 is in critical condition and will move to the top of the list. Someone with a MELD of 10 might wait months or years.But MELD isn’t the whole story. If you have liver cancer-specifically hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)-you must meet the Milan criteria: one tumor under 5 cm, or up to three tumors all under 3 cm, with no spread to blood vessels. If your alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) blood marker is above 1,000 and doesn’t drop below 500 after treatment, you’re usually not eligible unless you get special review.

Then there’s the hard part: sobriety. If your liver failed because of alcohol, most centers require six months of complete abstinence. But that rule isn’t universal. Some centers now accept three months if you’ve shown real change-therapy, support groups, stable housing. A 2023 study from Yale found no difference in five-year survival between those who waited three months versus six. Still, many programs stick to the old standard, and patients have reported being denied based on inconsistent policies.

Other deal-breakers? Active drug use, untreated mental illness, metastatic cancer, or severe heart or lung disease. You don’t need to be perfect-but you need to be stable. And you need a support system. No one recovers from a liver transplant alone. You need someone to drive you to appointments, help you take pills, notice if you’re getting yellow or confused. If you’re homeless, or isolated, you won’t get approved.

The Surgery: What Happens in the Operating Room

A liver transplant takes between six and twelve hours. The surgeon removes your damaged liver and replaces it with a healthy one. Most often, they use the “piggyback” technique-keeping your large vein (the inferior vena cava) in place and attaching the new liver to it. This reduces bleeding and speeds recovery.There are two types of donors: deceased and living. About 90% of transplants come from people who’ve died. But living donor transplants are growing. A healthy person can donate up to 60% of their liver-the part that regrows in weeks. The donor’s liver returns to normal size in about two months. The recipient’s new liver grows to full size, too.

For living donors, the rules are tight. They must be between 18 and 55, have a BMI under 30, no history of liver, heart, or kidney disease, and no smoking or drug use. The donor’s remaining liver must be at least 35% of its original volume. The graft must be at least 0.8% of the recipient’s body weight. These aren’t suggestions-they’re safety limits.

Living donor transplants cut waiting time dramatically. In high-MELD patients, the average wait for a deceased donor is 12 months. With a living donor, it’s about three. But it’s not risk-free. There’s a 0.2% chance the donor dies. About 20-30% have complications-bile leaks, infections, hernias. Still, centers like Columbia University are pushing boundaries. Some now accept donors with BMI up to 35 if they have excellent liver quality and strong support.

For patients with liver cancer from cholangiocarcinoma, new rules came in early 2025. You now need six months of tumor stability after radiation or chemo before you can even be considered. That’s stricter than before. But it’s meant to prevent transplants from failing because the cancer comes back too fast.

After the Surgery: Immunosuppression and Lifelong Care

The new liver is a foreign body. Your immune system will try to kill it. That’s why you take immunosuppressants-for life.Right after surgery, you get induction therapy. Low-risk patients get basiliximab, two IV doses on day zero and day four. High-risk patients-those with prior transplants, high antibody levels, or severe disease-get anti-thymocyte globulin for five days. Then comes maintenance: a triple combo of tacrolimus, mycophenolate, and prednisone.

Tacrolimus is the backbone. Doctors track your blood levels closely. In the first year, they want you between 5 and 10 ng/mL. After that, they lower it to 4-8. Too low? Rejection. Too high? Kidney damage, tremors, diabetes.

Mycofenoate mofetil stops white blood cells from attacking. It causes nausea and diarrhea in 30% of people. It can also lower your white blood cell count, making you prone to infections.

Prednisone used to be standard. But now, 45% of U.S. transplant centers skip it after the first month. Why? It causes weight gain, bone loss, cataracts, and diabetes. In one study, cutting prednisone dropped diabetes risk from 28% to 17%.

Side effects are real. At five years, 35% of patients have kidney damage from tacrolimus. One in four develop diabetes. One in five get nerve problems-tremors, headaches, trouble sleeping. Mycophenolate causes stomach issues for 3 in 10. And you have to take these pills exactly right. Miss one dose, and rejection can start within days.

Rejection isn’t always obvious. You might feel tired. Your eyes or skin might turn yellow. Your urine gets dark. Your temperature spikes. These aren’t just cold symptoms-they’re red flags. You need to call your team immediately.

Life After Transplant: The Real Challenge

The surgery is just the beginning. The real work is staying alive.You’ll need weekly blood tests for three months. Then every two weeks for the next three months. After that, monthly for a year. Then every three months. Forever. You’ll need to see your hepatologist, pharmacist, nurse coordinator, and dietitian regularly.

Medication costs? $25,000 to $30,000 a year-just for the drugs. Not counting hospital visits, scans, or emergencies. Insurance often denies coverage for pre-transplant evaluations. One survey found 32% of candidates were turned down for basic tests before even getting on the list.

But it’s not just about pills. You need to avoid crowds during flu season. Wash your hands constantly. Don’t clean cat litter. Don’t garden without gloves. Don’t eat raw fish or unpasteurized cheese. Your immune system is suppressed. A simple cold can turn deadly.

Success isn’t just survival. It’s quality. People who get transplants live longer, feel better, and return to work. Eighty-five percent are alive one year after surgery. Seventy percent make it five years. Some live 20, 30, even 40 years. The first long-term survivor lived over 25 years after his transplant in 1967.

But it’s not equal. Where you live matters. In the Midwest, MELD 25-30 patients wait about eight months. In California, it’s 18. That’s a year and a half longer. In the Southwest, you’re 40% less likely to get a liver in 90 days than someone with the same MELD score in the Mid-Atlantic.

New tools are helping. The FDA approved a portable liver perfusion device in 2023. It keeps donor livers alive outside the body for 24 hours instead of 12. That means more organs can be used, especially from older or damaged donors. In Pittsburgh, using this machine cut biliary complications by 28%.

What’s Next? The Future of Liver Transplants

The field is changing fast. Researchers are testing ways to let people stop taking immunosuppressants. At the University of Chicago, 25% of pediatric transplant patients have been successfully weaned off drugs by age five using regulatory T-cell therapy. That’s not yet common in adults-but it’s coming.Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), or fatty liver disease, is now the second leading cause of liver transplants in the U.S., behind alcohol. In 2010, it caused 3% of transplants. In 2023, it was 18%. That number will keep rising.

Some centers are rethinking old rules. British Columbia changed its policy in November 2025 to better support Indigenous patients. They now include cultural healers in psychosocial evaluations and adjust abstinence requirements based on individual circumstances-not rigid timelines.

And while artificial liver devices exist, they’re still just bridges-not replacements. None have kept a person alive more than 30 days without a transplant.

So what does it all mean? Liver transplantation is not a cure. It’s a second chance. A heavy one. It demands discipline, support, and lifelong vigilance. But for those who make it through, it’s the difference between dying and living-really living-again.

Can you get a liver transplant if you’re over 65?

Yes, age alone doesn’t disqualify you. Many transplant centers accept patients into their 70s if they’re otherwise healthy. The key is overall fitness-not age. Heart function, lung capacity, muscle strength, and mental health matter more. One 2023 study showed patients over 65 had similar survival rates to younger patients when they passed full evaluation.

How long is the wait for a liver transplant?

It varies wildly by location and how sick you are. For low-MELD patients (under 15), it can take years. For high-MELD patients (over 25), it’s usually 6-18 months. In the Midwest, wait times average 8 months. In California, they’re closer to 18. Living donor transplants can reduce that to about three months.

Can you drink alcohol after a liver transplant?

No. Even if your original liver disease wasn’t caused by alcohol, drinking after transplant can damage your new liver. It increases the risk of rejection, scarring, and failure. Most centers require lifelong abstinence. Some allow very limited alcohol after five years-but only if you’ve had perfect compliance and no signs of liver damage.

What happens if the new liver fails?

If the transplanted liver fails, you may be eligible for a second transplant-but it’s harder. You’ll need to be re-evaluated. Your chances depend on why the first one failed, your overall health, and whether you’ve followed your care plan. Second transplants have lower survival rates than first ones, but many people still live for years after.

Do you need to take immunosuppressants forever?

Most people do-but not all. A small percentage of patients, especially children, can eventually stop taking these drugs thanks to new therapies like regulatory T-cell treatment. In adults, this is rare. But research is advancing fast. For now, assuming lifelong immunosuppression is the safest plan.

How do you know if you’re rejecting the new liver?

Symptoms include fever above 100.4°F, yellowing skin or eyes (jaundice), dark urine, extreme fatigue, nausea, abdominal swelling, or pain near the transplant site. But rejection can happen without symptoms. That’s why regular blood tests are critical. If your liver enzymes rise unexpectedly, your doctor will do a biopsy to confirm.

What You Can Do Now

If you’re considering a transplant-or supporting someone who is-start by finding a certified transplant center. Ask about their success rates, waiting times, and how they handle insurance. Don’t wait until you’re in crisis. The evaluation process takes months. Get your heart checked, your mental health evaluated, your support network in place.Transplant isn’t just medicine. It’s a lifestyle. It’s discipline. It’s trust in a team. And for those who make it through? It’s a gift no pill can give.

Sean Feng

January 10, 2026 AT 23:43They say you need a support system but what if you’re homeless? Guess you just die slower. The system’s rigged from the start.

Adewumi Gbotemi

January 11, 2026 AT 17:47This is heavy. In my country, people wait years just to see a doctor. To get a new liver? It feels like a dream. But thank you for explaining it so clear.

Jason Shriner

January 12, 2026 AT 19:58So let me get this straight… you have to be sober for 6 months but your liver was destroyed by a 20-year habit and now you’re being judged like a teenager who stole a beer? Classic. Also, who decided ‘stable housing’ is a medical requirement? Next they’ll ask for your Spotify playlist.

Vincent Clarizio

January 13, 2026 AT 16:20Let’s be real here - this entire system is a philosophical paradox wrapped in bureaucratic red tape. We’re told the liver is irreplaceable, yet we treat human life like a commodity on a waiting list ranked by blood values. The MELD score reduces suffering to three lab numbers. We’ve turned survival into a spreadsheet. And don’t even get me started on the fact that your zip code determines whether you live or die. This isn’t medicine - it’s lottery economics with scalpels.

Alex Smith

January 14, 2026 AT 00:26Someone mentioned the living donor thing - here’s a wild thought: what if we started paying donors? Not cash, but tax breaks, medical coverage for life, paid leave. The risk is real, the reward is life. We do it for kidneys. Why not livers? And why are we still pretending abstinence timelines are science and not moral policing?

Madhav Malhotra

January 15, 2026 AT 08:02In India, we say ‘the body remembers what the mind forgets.’ This post made me think of my uncle - he stopped drinking after his diagnosis, went to temple every day, and waited 2 years. He got his transplant last year. He’s alive now. Not because of luck - because he fought. And he had his family holding his hand through every blood test.

Priya Patel

January 15, 2026 AT 08:51I cried reading this. My best friend is on the list. She’s 52, has two kids, and refuses to give up. I’ve been driving her to every appointment. The meds alone cost more than our rent. But she still laughs. She says the liver doesn’t define her - she defines what she does with it. I’m so proud of her.

Christian Basel

January 16, 2026 AT 11:08Immunosuppression protocols are suboptimal due to non-linear pharmacokinetics of calcineurin inhibitors coupled with CYP3A4 polymorphisms and variable drug interactions. The current triple-therapy paradigm fails to account for T-cell receptor clonal expansion dynamics post-engraftment, leading to subclinical rejection in 22% of cases undetected by standard LFTs. We need personalized immunomodulatory algorithms based on HLA mismatch profiles and microbiome signatures.

Roshan Joy

January 18, 2026 AT 01:43Love how you mentioned the new perfusion device - that’s huge. In India, we don’t have access to this tech yet, but I’ve seen how even small changes like better transport systems for organs can save lives. Keep pushing for equity. Everyone deserves a shot - no matter where they live. 🙏