When you walk into a pharmacy in the U.S. and see a $6 copay for your blood pressure pill, it’s easy to think you’re getting a deal. But here’s the twist: generic drugs in the United States are actually cheaper than in most other developed countries. That’s not a myth. It’s backed by data from the RAND Corporation, the FDA, and Medicare’s own reports. At the same time, if you’re on a brand-name drug like Jardiance or Stelara, you’re paying nearly four times what someone in Japan or Australia pays for the exact same medicine. The U.S. doesn’t have cheap drugs overall-it has cheap generics and outrageously expensive brands. And that split tells the whole story.

Why U.S. Generic Prices Are Lower Than Everywhere Else

Here’s something most people don’t realize: 90% of all prescriptions filled in the U.S. are for generic drugs. That’s not a small fraction-it’s the norm. And because of that volume, the market for generics here is brutal in the best way possible. When three or more companies start making the same generic pill, prices don’t just drop-they collapse. According to the FDA’s 2019 analysis, once you hit three generic competitors, the price falls to just 15-20% of the original brand-name drug’s list price. In some cases, it’s even lower.

Compare that to countries like Germany or Canada, where generic adoption is only around 40-50%. Fewer manufacturers mean less competition, which means higher prices. In France and Japan, where the government tightly controls pricing and pushes generics hard, you’ll still pay more per pill than you do in the U.S. The reason? The U.S. doesn’t set prices-it lets the market crush them. And with over 773 new generic approvals in 2023 alone, the system is pumping out cheaper options faster than anywhere else.

Take a common drug like metformin, used by millions for type 2 diabetes. In the U.S., a 90-day supply can cost under $10 at Walmart or Costco. In the UK, the same supply costs about $18. In Canada, it’s $22. In Germany? Over $25. And that’s not an outlier. It’s the pattern. The average U.S. generic copay is $6.16. The average brand-name copay? $56.12. That’s not a typo. Nine times more for the same effect.

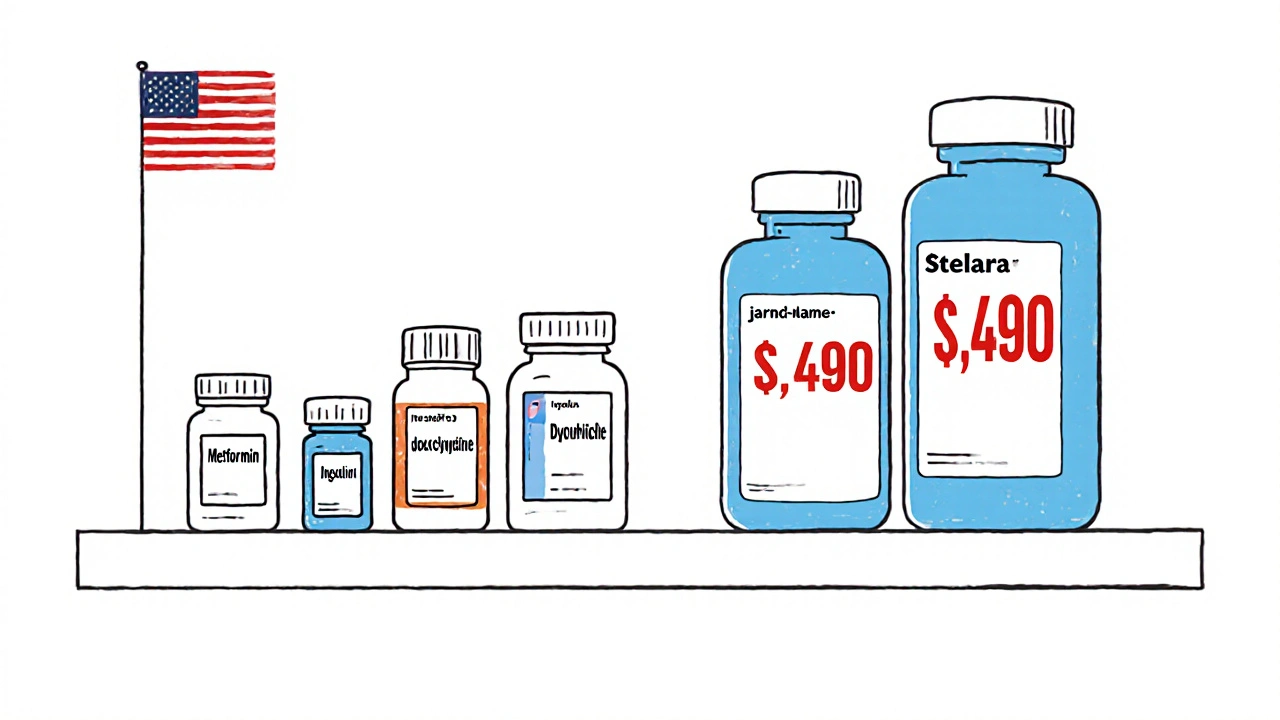

The Brand-Name Problem: Why Americans Pay 4x More

If generics are so cheap, why does the U.S. spend more on drugs than any other country? The answer is simple: brand-name drugs. They’re the exception, but they’re the reason the bill is so high. A 2022 RAND study found that U.S. brand-name drug prices are 422% higher than in other OECD countries. That means if a drug costs $100 in Japan, you’ll pay $422 for it in the U.S.-before insurance, before rebates, before anything.

Medicare’s first round of negotiated prices in 2024 showed just how bad it is. For Jardiance, a diabetes drug, Medicare paid $204 per month. The average price in 11 other countries? $52. For Stelara, a biologic used for psoriasis and Crohn’s, the U.S. negotiated price was $4,490 per dose. The global average? $2,822. And even after negotiation, the U.S. still paid more in 9 out of 10 cases.

This isn’t because American drug companies are greedy-it’s because the system lets them charge what they want until something stops them. In most countries, governments set price caps. In the U.S., insurers and pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) negotiate behind closed doors. The result? You pay the list price until your insurance kicks in. And if you’re uninsured? You’re stuck with the full, inflated price.

The Hidden Truth: List Prices vs. Net Prices

Here’s where things get confusing. You’ll hear headlines saying U.S. drug prices are 2.78 times higher than other countries. That’s true-but only if you’re looking at list prices. List prices are what drug companies charge pharmacies before any discounts. In reality, most Americans never pay list price. Medicare, Medicaid, and big insurers get massive rebates. The University of Chicago’s 2024 study found that when you look at net prices-the actual amount paid after rebates-the U.S. pays 18% less than Canada, Germany, the UK, France, and Japan.

How? Because the U.S. has a massive, fragmented system that forces drugmakers to give deep discounts to keep their drugs on formularies. It’s messy, but it works. The problem? Those discounts don’t reach the uninsured or people on high-deductible plans. They also don’t show up on the price tags you see at the pharmacy counter. So if you’re paying out-of-pocket, you’re seeing the worst-case scenario: the full list price.

And here’s the catch: those rebates don’t lower the cost of the drug itself. They just shift who pays. Drugmakers still make huge profits on brand-name drugs. The rebates go to insurers and PBMs, not patients. So while the system lowers overall spending, it doesn’t make drugs affordable for everyone.

How Other Countries Keep Prices Down

Japan and France don’t have a free market for drugs. They have price controls. The Japanese government negotiates prices directly with manufacturers every two years. If a company refuses, the drug gets pulled from the national formulary. That’s why Japan has the lowest drug prices in the OECD-even for generics.

Germany uses a reference pricing system. If a new drug comes out, the government looks at what similar drugs cost in other countries and sets a price based on that. If the drug is too expensive, it doesn’t get covered by public insurance. That’s why Germany’s brand-name prices are still lower than the U.S.’s, even though they don’t have as many generic competitors.

The U.K. has the National Health Service (NHS), which buys drugs in bulk and sets one price for the whole country. It’s not perfect-sometimes patients wait longer for new drugs-but it keeps prices low. The NHS pays about 40% less than the U.S. for the same brand-name drugs, even after rebates.

Canada is somewhere in the middle. They have price caps, but their system is less aggressive than Japan’s. That’s why Canadian generic prices are higher than in the U.S.-but brand-name prices are still lower.

What Happens When There’s No Competition?

Low generic prices aren’t guaranteed. They only work when there are enough manufacturers. If only one company makes a generic, it can raise prices-sometimes dramatically. The FDA has documented cases where a generic drug jumped from $2 to $200 overnight because all other manufacturers left the market.

This happened with doxycycline, an antibiotic, in 2013. When only two companies were left making it, prices tripled. When one dropped out, the remaining one raised prices by over 1,000%. It took years and a federal investigation to fix it. That’s why regulators now watch for “market concentration.” Too few makers? That’s a red flag.

That’s also why the FDA is pushing hard to approve more generics. Every new competitor lowers the price. The 773 generic approvals in 2023 are expected to save $13.5 billion over five years. That’s real money. But it only works if those generics actually reach the market-and don’t get blocked by legal battles or patent tricks.

Who Benefits? Who Gets Left Behind?

If you have good insurance, you’re probably fine. Your generic copay is $6. You rarely see the real cost. But if you’re uninsured, underinsured, or on a high-deductible plan? You’re in trouble. You pay list price. And for brand-name drugs, that’s a financial disaster.

Take insulin. Even though there are now multiple generic versions, the list price for Humalog is still over $275 per vial in the U.S. In Canada, it’s $35. In the U.K., it’s $15. The cost to make it? Around $5. The profit margin? Huge. And it’s not just insulin. Many cancer drugs, biologics, and specialty medications follow the same pattern.

Meanwhile, Medicare’s new negotiation program is starting to make a dent. But it only covers 10 drugs so far. The next round, due in early 2026, could add 15 more. That’s progress-but it’s still a drop in the bucket compared to the 10,000+ drugs on the market.

The Bigger Picture: Innovation vs. Access

Drug companies argue that high U.S. prices fund global innovation. They say if Americans didn’t pay more, new drugs wouldn’t get developed. But the data doesn’t fully back that up. The U.S. spends more on drugs than the next 10 countries combined. Yet, most new drugs are developed by multinational companies that sell everywhere. The U.S. isn’t the only source of R&D funding.

Some experts, like Dr. Dana Goldman from USC, say the U.S. generic system is a model other countries should copy. Others, like RAND’s Andrew Mulcahy, say the brand-name pricing is unsustainable. The truth? Both are right. The U.S. has the best generic market in the world. But its brand-name pricing is the worst.

And now, with new policies like the Most-Favored-Nation Executive Order, the U.S. is trying to force drugmakers to lower prices globally. That could backfire. If companies raise prices overseas to make up for lost U.S. profits, it could hurt patients in low-income countries. It’s a global puzzle with no easy answer.

What You Can Do Right Now

If you’re on a generic drug, you’re already getting a great deal. But if you’re paying for brand-name meds, here’s what to do:

- Ask your doctor if a generic version exists. Even if it’s not on your formulary, it might be cheaper out-of-pocket.

- Use pharmacy discount apps like GoodRx or SingleCare. They often beat insurance prices.

- Check if your drug is on Medicare’s negotiation list. If it is, your price may drop soon.

- For chronic conditions, ask about 90-day supplies. They’re usually cheaper per pill.

- If you’re uninsured, look into patient assistance programs from drugmakers. Many offer free or low-cost meds.

Don’t assume your copay is the full price. Always ask. Always compare. And remember: in the U.S., the cheapest version of a drug is often the generic-and it’s cheaper here than anywhere else on Earth.

Why are generic drugs cheaper in the U.S. than in other countries?

Generic drugs are cheaper in the U.S. because of high competition. When three or more companies make the same generic, prices drop to 15-20% of the brand-name price. The U.S. fills 90% of prescriptions with generics, creating massive volume that drives down costs. Other countries have fewer generic manufacturers and stricter price controls that don’t allow for the same level of competition.

Do Americans pay more for all drugs?

No. Americans pay less for generic drugs than most other developed countries. But they pay significantly more for brand-name drugs. The U.S. spends more overall on pharmaceuticals because brand-name drugs account for most of the spending, even though they make up only 10% of prescriptions.

What’s the difference between list price and net price?

List price is what drug companies charge pharmacies before any discounts. Net price is what’s actually paid after rebates and discounts from insurers and pharmacy benefit managers. Most Americans never pay list price. But if you’re uninsured, you do-and that’s where the real cost shock happens.

Why do some generic drugs suddenly become very expensive?

When only one or two companies make a generic drug, they can raise prices. If one manufacturer leaves the market, the remaining one may monopolize it and jack up the price. This has happened with antibiotics like doxycycline and older drugs like insulin. The FDA monitors this and tries to speed up approvals to prevent shortages.

Can I buy cheaper drugs from other countries?

Legally, importing prescription drugs from other countries is not allowed in the U.S., except in rare cases. But many people do it anyway, especially for insulin and other high-cost meds. Some states are exploring official import programs from Canada. For now, using discount apps like GoodRx or checking patient assistance programs is the safest and legal way to save.

Will Medicare negotiation lower drug prices for everyone?

Medicare negotiation only affects the 10 drugs selected so far-and only for Medicare Part D enrollees. But it sets a precedent. Drugmakers may lower prices elsewhere to avoid future negotiations. It won’t fix everything, but it’s the first major step toward controlling brand-name drug costs in the U.S.

Cynthia Boen

November 27, 2025 AT 01:28This whole post is a corporate PR stunt. You think generics are cheap? Try getting them when your insurance only covers one brand and charges $500 for the generic you need. The system is rigged.

Amanda Meyer

November 28, 2025 AT 21:29The data is solid, but the framing ignores the human cost. Yes, generics are cheaper-but only if you have insurance, transportation to a pharmacy that stocks them, and the time to navigate formularies. Millions don’t. The system works for spreadsheets, not people.

Stephanie Deschenes

November 28, 2025 AT 22:02As a pharmacist for 18 years, I can confirm: when three generics hit the market, prices plummet. I’ve seen metformin drop from $40 to $7 in six months. It’s not magic-it’s competition. The FDA’s approval pipeline is the real hero here.

Jesús Vásquez pino

November 30, 2025 AT 00:28Why are you guys so shocked? The U.S. doesn’t regulate drug prices because the lobbyists own Congress. The fact that generics are cheap is just a loophole-pharma makes up for it tenfold on brand-name drugs. It’s not a feature, it’s a flaw.

Ginger Henderson

November 30, 2025 AT 00:38Wait, so the U.S. has cheap drugs? Lol. My insulin is still $300. This article is just making people feel better about being exploited.

Bethany Buckley

December 1, 2025 AT 22:21One must interrogate the epistemological underpinnings of pharmaceutical pricing paradigms. The neoliberal commodification of biopharmaceuticals, mediated through PBMs and opaque rebate architectures, creates a pseudo-market wherein consumer agency is algorithmically suppressed. Net prices ≠ access. List prices ≠ justice.

hannah mitchell

December 2, 2025 AT 22:56My dad takes metformin. He pays $4 at Walmart. He says, ‘I’m lucky.’ That’s sad.

vikas kumar

December 4, 2025 AT 16:46From India, I can tell you generics here are dirt cheap-like $1 for a month’s supply of lisinopril. But we don’t have the infrastructure to make sure everyone gets them. The U.S. system is messy, but at least the pills are there. In some places, they’re not even stocked.

Vanessa Carpenter

December 6, 2025 AT 08:11I used GoodRx to buy my thyroid med for $12 instead of $80. I didn’t even know that was an option until last year. If more people knew about these apps, a lot of suffering could be avoided. Just… ask.

Bea Rose

December 7, 2025 AT 01:3090% generics. 10% brand. 90% of spending on the 10%. Math doesn't lie. The system is designed to extract wealth from the sick. It's not a bug. It's the business model.

Michael Collier

December 8, 2025 AT 00:45It is imperative to recognize the structural inefficiencies inherent in the current pharmaceutical distribution paradigm. While the United States demonstrates unparalleled efficiency in the production and dissemination of generic therapeutics, the absence of price regulation for proprietary medications constitutes a significant market failure. The introduction of Medicare negotiation, though incremental, represents a necessary corrective mechanism.

Mqondisi Gumede

December 8, 2025 AT 06:39U.S. generics cheap? Sure. But you know what's cheaper? Buying from Mexico. Americans act like they’re too good to import medicine. Meanwhile, our politicians let Big Pharma rob us blind. We’re not the land of the free-we’re the land of the overcharged.

stephen riyo

December 9, 2025 AT 10:50Wait wait wait-so you’re saying the reason U.S. generics are cheap is because of competition? But then why did my dad’s blood pressure med go from $10 to $40 last year? There was still three companies making it…?!

Damon Stangherlin

December 10, 2025 AT 07:10That’s why the FDA tracks market concentration-when only one or two companies are left, they can jack up prices. Happened with doxycycline, clindamycin, even some birth control pills. It’s not about how many were approved-it’s about who’s actually making them. The system’s fragile.

Ryan C

December 11, 2025 AT 01:06Let’s be real. The U.S. is the only country where you can legally buy a $422 Jardiance pill and then get a $400 rebate from your insurer… and still pay $200 out of pocket. The entire system is a glitch in the matrix. 🤖💸