Why Dialysis Access Matters More Than You Think

If you’re on hemodialysis, your access point isn’t just a tube or a needle site-it’s your lifeline. Every time you sit down for treatment, your blood flows through this connection to be cleaned by the dialysis machine. The type of access you have affects how long you stay healthy, how often you end up in the hospital, and even how long you live.

There are three main ways to connect your blood to dialysis: an AV fistula, an AV graft, or a central venous catheter. Each has different pros, cons, and care needs. And while many people start with a catheter because it’s quick to put in, it’s not the best long-term choice. The truth is, if you can get a fistula, you should. It’s the gold standard for a reason.

AV Fistula: The Gold Standard

An arteriovenous (AV) fistula is made by a surgeon connecting an artery directly to a vein-usually in your forearm, often on your non-dominant arm. This isn’t a quick fix. It takes 6 to 8 weeks for the vein to grow stronger and wider so it can handle the needles used during dialysis. That waiting period is tough, but it’s worth it.

Once mature, a fistula can last for decades. Many patients use the same fistula for 10, 15, even 20 years with no major issues. They’re less likely to clot, less likely to get infected, and far less likely to cause serious complications than other options. According to studies, people on dialysis with fistulas have a 36% lower risk of death compared to those using grafts, and more than 50% lower risk than those using catheters.

The key to making a fistula work? Monitoring it every day. Feel for a vibration-the "thrill"-at the access site. That means blood is flowing properly. If the thrill disappears, or if you notice swelling, redness, or pain, call your care team right away. Most fistulas don’t need daily cleaning beyond washing with soap and water. But you should never let anyone take your blood pressure or draw blood from that arm.

AV Graft: The Backup Plan

Not everyone’s veins are strong enough for a fistula. If your blood vessels are too small, too damaged, or too scarred from past procedures, a graft is the next best option. A graft is a synthetic tube-usually made of PTFE-that connects an artery to a vein. It’s placed under the skin and can be used in just 2 to 3 weeks after surgery.

But grafts come with trade-offs. They’re more prone to clotting and infection than fistulas. About 30 to 50% of grafts need some kind of intervention-like a clot-busting procedure or balloon angioplasty-within the first year. That means more trips to the hospital, more needles, more downtime.

Patients with grafts often notice the site feels harder or more swollen than a fistula. You still need to check for thrill daily, but you also need to be extra careful about keeping the area clean. Even a small nick or scratch near the graft can lead to infection. Some people find grafts more painful during needle insertion, especially if the graft has narrowed over time.

Despite the extra care, grafts are still a solid choice when fistulas aren’t possible. They’re durable, reliable, and far better than long-term catheter use.

Central Venous Catheter: Temporary, But Sometimes Necessary

A central venous catheter (CVC) is a soft tube inserted into a large vein in your neck, chest, or groin. It’s ready to use immediately, which is why it’s often used when someone starts dialysis urgently. But it’s not meant to be permanent.

Catheters are the most dangerous option. They’re the leading cause of bloodstream infections in dialysis patients. Studies show catheter users have more than twice the risk of dying from an infection compared to those with fistulas. Each catheter day carries a 0.6% to 1.0% risk of serious infection. That adds up fast.

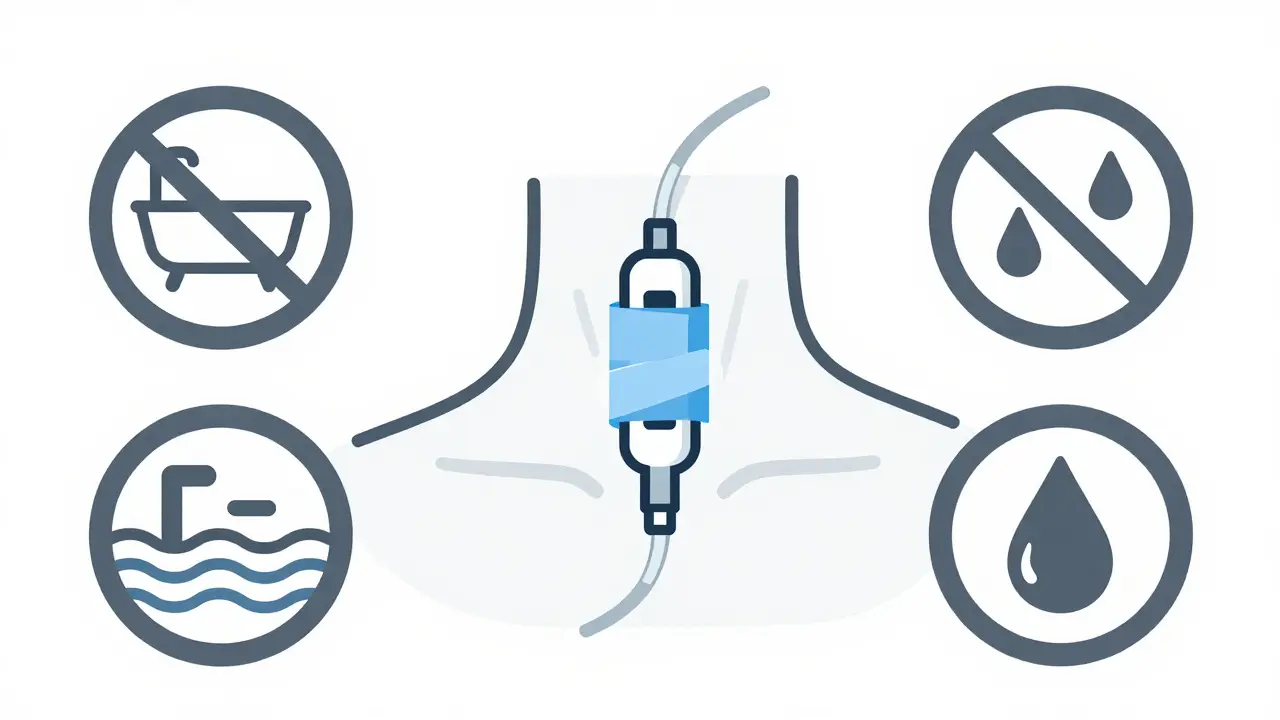

Every day, you have to clean the catheter exit site with antiseptic, change the dressing, and make sure the caps are tightly sealed. You can’t shower normally-you have to wrap the catheter in plastic. Swimming, baths, even heavy sweating can be risky. Many patients say the lifestyle restrictions are worse than the dialysis itself.

Some people end up stuck with a catheter because their veins are too damaged for a fistula or graft. Others wait too long to get a permanent access. But if you’re on a catheter, your care team should be working with you to get you onto a fistula or graft as soon as possible. Don’t accept long-term catheter use as normal.

What You Can Do to Protect Your Access

Good access care starts before surgery. Vein mapping-an ultrasound scan of your arms-is the first step. It shows your surgeon which veins are strong enough for a fistula. If you have diabetes or high blood pressure, your veins may be harder to work with. That’s why it’s important to get this done early, not when you’re already on dialysis.

Exercise helps. Simple hand squeezes, wrist curls, and arm lifts can improve blood flow and increase your chances of a successful fistula. One study found that patients who did daily exercises before surgery had 15% to 20% higher fistula maturation rates.

After surgery, follow your nurse’s training. Most people need 2 to 3 sessions to learn how to check their access, clean it, and spot warning signs. If you’re using a catheter, you’ll need more training-sometimes weekly-until you’re confident.

Keep a log. Write down when you feel the thrill, if there’s any swelling, redness, or pain. Bring it to your appointments. Your care team can catch problems early if you’re paying attention.

Common Problems and How to Spot Them

Every type of access has its own risks:

- Fistula aneurysms: About 15% to 20% of long-term fistula users develop bulges where needles are inserted. These can be dangerous if they rupture. Avoid repeated needle placement in the same spot. Ask your nurse to rotate sites.

- Graft clotting: If your graft stops vibrating, or if dialysis takes longer than usual, it might be clotting. Don’t wait-call your clinic immediately.

- Catheter infections: Fever, chills, redness, or pus around the catheter site? That’s a red flag. Infections can spread fast and become life-threatening.

One patient I spoke with said she ignored a slight warmth near her graft for three days. By the time she went in, she had a severe infection and ended up in the hospital for two weeks. Early action saves lives.

Why Some People Don’t Get Fistulas-And What Needs to Change

Even though fistulas are the best option, not everyone gets one. Data shows Black patients are 30% less likely to receive a fistula than White patients-even when they have the same health conditions. That’s not because of medical need. It’s because of delays in referral, lack of access to vascular surgeons, or assumptions about who "can handle" the care.

Cost matters too. Catheters are cheaper to place upfront. But they cost the U.S. healthcare system over $1 billion a year in extra hospital stays and treatments. Switching just 10% of catheter users to fistulas could save billions.

There’s hope. New tools like wireless sensors (like Vasc-Alert) can monitor fistula blood flow in real time and warn of clots before they happen. Bioengineered vessels are also in trials-vessels grown from human cells that might replace synthetic grafts in the future.

The goal by 2030? Keep fistulas as the primary access for 65% to 70% of dialysis patients. That’s possible-if we act now.

What’s Next for You?

If you’re starting dialysis soon, ask your doctor: "Can I get a fistula?" If they say no, ask why. Push for vein mapping. Ask about pre-surgery exercises. Don’t accept a catheter as your only option.

If you already have a graft or catheter, don’t wait. Talk to your care team about switching. Many patients think it’s too late-but it’s never too late to improve your access.

Take control. Check your access daily. Learn the signs of trouble. Ask questions. Your access isn’t just a medical device-it’s your connection to a longer, healthier life.

What’s the difference between an AV fistula and an AV graft?

An AV fistula is made by surgically connecting your own artery and vein, usually in the arm. It takes 6-8 weeks to mature but lasts for decades with proper care. An AV graft uses a synthetic tube to connect the artery and vein. It can be used in 2-3 weeks but is more prone to clotting and infection, and usually needs replacement every 2-3 years.

Why is a catheter considered the worst option for long-term dialysis?

Catheters carry the highest risk of serious infection, bloodstream infections, and death compared to fistulas and grafts. They also require strict daily care, limit bathing and swimming, and are more likely to cause complications like clots and vein damage. While useful for emergencies, they’re not meant for long-term use.

How do I know if my fistula is working properly?

Feel for a "thrill"-a steady vibration-over the fistula site. You should also hear a "bruit," a whooshing sound when you listen with a stethoscope. If the thrill disappears, or if you notice swelling, pain, or coldness in your hand, contact your care team immediately. These could mean a clot or blockage.

Can I shower with a dialysis catheter?

You can shower, but you must keep the catheter site completely dry. Use waterproof covers or plastic wrap sealed with tape. Never soak the catheter in water-no baths, hot tubs, or swimming. Moisture increases infection risk. Always check the dressing after showering and replace it if it’s wet or loose.

What should I do if my dialysis access stops working?

Don’t wait. Call your dialysis center or vascular specialist right away. If your fistula or graft loses its thrill, or if your catheter isn’t flowing properly, it could be clotted. Early intervention can often restore blood flow with a simple procedure. Delaying treatment can lead to permanent damage or the need for emergency surgery.

Are there new technologies to help with dialysis access?

Yes. Wireless sensors like Vasc-Alert can monitor fistula blood flow in real time and alert you to early signs of clotting. Bioengineered vessels made from human cells are in clinical trials and may replace synthetic grafts in the future. Preoperative exercise programs are also proven to improve fistula success rates by 15-20%.

Final Thoughts: Your Access, Your Health

Dialysis access isn’t just a medical procedure-it’s a daily responsibility. Whether you have a fistula, graft, or catheter, your actions matter. Check it. Clean it. Protect it. Speak up if something feels off.

There’s no perfect system. But the best access for you is the one that keeps you out of the hospital, lets you live your life, and gives you the longest chance at health. Start with the facts. Ask the right questions. And never settle for less than the best option available.

RAJAT KD

January 10, 2026 AT 13:55Just felt my thrill this morning-still there. Been doing the wrist curls daily since my fistula surgery. Don’t skip the checks.

Jenci Spradlin

January 10, 2026 AT 17:58my graft clotted last month and i swear i thought i was done for. got the angioplasty, now it’s fine. but man, the fear? real. don’t wait till it’s bad.

Aron Veldhuizen

January 11, 2026 AT 09:51Let’s be honest-this whole system is a profit-driven farce. Catheters are cheaper for hospitals, so they push them. Fistulas require skilled surgeons and follow-up care-costs too much. The ‘gold standard’ is just a marketing slogan for patients who can’t fight back.

And don’t get me started on ‘vein mapping.’ If you’re poor or uninsured, good luck getting that scheduled before your kidneys give out. This isn’t medicine-it’s triage capitalism.

They call it a ‘lifeline’ but for most, it’s a death sentence with a waiting list.

Micheal Murdoch

January 12, 2026 AT 13:28I’ve been on dialysis for 12 years. Started with a catheter. Then a graft. Now I’ve got a fistula that’s been humming since 2018. It didn’t happen overnight. I had to learn to advocate for myself-ask for referrals, push for exercises, even printed out studies to show my nephrologist.

One thing nobody tells you: your access isn’t just a medical device. It’s a conversation you have every single day. The thrill? That’s your body talking back. Listen to it.

And if you’re reading this and you’re scared? You’re not alone. But you’re stronger than you think. I used to cry after every needle. Now I joke with the nurses. That’s progress.

Don’t wait for someone to save you. Save yourself. One check, one question, one stretch at a time.

Heather Wilson

January 14, 2026 AT 09:58While the article is well-structured and cites statistics, it completely omits the psychological toll of daily access monitoring. The hypervigilance required to check for thrill, the anxiety over a missed vibration, the shame of having to explain to coworkers why you can’t wear short sleeves-it’s not just physical. It’s existential.

And yet, the narrative here is overwhelmingly optimistic. That’s dangerous. For every success story, there are five people who’ve had multiple failed fistulas, who’ve been told ‘your veins are too damaged’ after years of insulin use, who are now stuck with a catheter and told to ‘just be grateful.’

The real issue isn’t access-it’s equity. Why are Black patients 30% less likely to get fistulas? Because the system was never designed for them to survive. The article avoids that truth.

Chris Kauwe

January 16, 2026 AT 08:21From a vascular physiology standpoint, the AV fistula remains the optimal hemodynamic conduit due to its low resistance, high-flow characteristics, and endothelial integrity. Grafts, by contrast, introduce a xenograft interface that promotes neointimal hyperplasia and thrombogenicity.

Furthermore, the 36% mortality reduction cited is corroborated by the 2021 KDOQI guidelines, which classify fistulas as Class I recommendation. Catheters, however, remain a Class III contraindication for chronic use.

It’s not opinion-it’s evidence-based vascular access management. The failure to implement this universally is a systemic failure of clinical governance, not patient noncompliance.

Elisha Muwanga

January 17, 2026 AT 08:04Interesting how this article makes it sound like we all have equal access to surgeons, insurance approvals, and time off work. Meanwhile, I work two jobs and still can’t get a vein mapping done because my insurance says ‘it’s not urgent.’

So yeah, fistula’s the gold standard. But gold doesn’t grow on trees when you’re living paycheck to paycheck.

Ian Long

January 18, 2026 AT 09:00Just wanted to say thanks to everyone sharing their stories. I’ve been reading this thread and I’m not on dialysis myself-but I have a friend who is. I didn’t realize how much emotional labor goes into just staying alive. I’m going to help her schedule her vein mapping next week. No more waiting.