Using an insulin pump isn’t like plugging in a phone charger and forgetting about it. It’s a medical device that runs on your decisions-every meal, every blood sugar check, every change in activity. If you’re on continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion (CSII), you’re not just managing diabetes-you’re managing a machine that listens to you, but only if you speak clearly. Miss a setting. Forget to change the site. Ignore a low alarm. And the pump keeps going. That’s the reality. And it’s why pump settings and safety aren’t optional. They’re your lifeline.

How Insulin Pumps Work-No Fluff

Insulin pumps deliver rapid-acting insulin (like Humalog or Novolog) through a tiny tube under your skin. No long-acting insulin needed. The pump gives you two types of insulin: a steady background drip called the basal rate, and quick bursts called boluses for meals or high blood sugar. The basal rate changes throughout the day because your body doesn’t need the same amount of insulin at 3 a.m. as it does at 7 p.m. Most pumps let you set different basal patterns for weekdays, weekends, exercise, or illness. It’s not magic. It’s math. And it’s personal.

Modern pumps work with continuous glucose monitors (CGMs). Some, like the Medtronic 670G or Omnipod 5, can automatically adjust basal insulin when your sugar drops or rises. But even these don’t give you a free pass. You still have to tell the pump what you ate. You still have to check your sugar. You still have to change the infusion set every two to three days. If you think the pump does everything, you’re setting yourself up for trouble.

Basal Rates: The Invisible Backbone

Your basal rate is the silent engine of your pump. It’s usually 40-50% of your total daily insulin, spread across 24 hours. Most people need more insulin in the early morning (dawn phenomenon) and less overnight. But if your basal is too high, you crash. Too low, and your sugar climbs all day. Testing it isn’t optional. Dr. John Walsh, author of Pumping Insulin, says the most common pump mistake? Improper basal testing.

Here’s how to test it properly: Fast for 24 hours. No food. No boluses. No exercise. Check your blood sugar every two hours. If your sugar stays within 1 mmol/L of your target, your basal is right. If it rises by more than 2 mmol/L, your basal is too low. If it drops, it’s too high. Do this on a day when you’re not sick or stressed. Do it when you’re rested. Most people need to test and adjust their basal rates at least twice a year-or anytime their routine changes.

Bolus Settings: Eating Without Guesswork

When you eat, you need to cover the carbs. That’s where your insulin-to-carbohydrate ratio (ICR) comes in. If your ICR is 1:10, one unit of insulin covers 10 grams of carbs. If it’s 1:15, you need less insulin per gram. Most adults start with 1:10 to 1:15, but your body might need 1:8 or 1:20. The only way to find yours? Track your meals, insulin, and blood sugar for at least a week. Use a logbook or app. Look for patterns. Did your sugar spike after pasta? That might mean your ICR is too high for carbs that digest slowly.

Then there’s the insulin sensitivity factor (ISF)-also called the correction factor. This tells you how much one unit of insulin lowers your blood sugar. If your ISF is 1:3, one unit drops your sugar by 3 mmol/L. If it’s 1:5, it drops by 5. Start with 1800 divided by your total daily insulin dose (in the U.S., they use 1500). So if you take 30 units a day, your ISF is roughly 1:60 (1800 ÷ 30 = 60 mg/dL, or about 1:3.3 mmol/L). But again, this is just a starting point. Adjust based on real results.

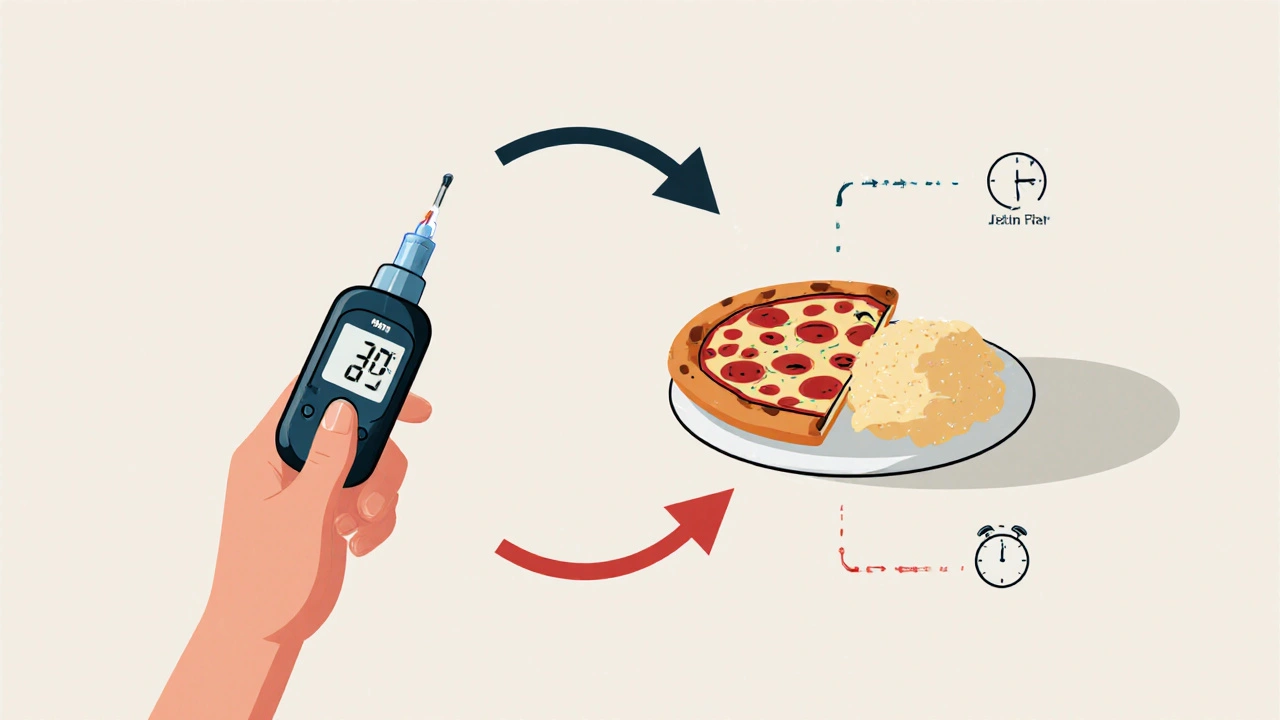

And don’t forget extended boluses. A steak with mashed potatoes? That’s a dual-wave bolus-half right away, half over two hours. Pizza? Same deal. Fast carbs spike fast. Fat and protein drag it out. Pumps can handle this. But only if you know how to use it. Most users don’t. And that’s why their sugar spikes hours after eating.

Infusion Sites and Site Care

Change your infusion set every two to three days. No exceptions. Even if it doesn’t hurt. Even if the site looks fine. Skin gets irritated. Scar tissue builds up. That’s called lipohypertrophy. And it makes insulin absorb unevenly. One study found 27% of new pump users developed this within months. That’s why rotation matters. Don’t use the same spot on your belly every time. Move around-abdomen, thighs, upper arms. Avoid scar tissue. Avoid moles. Avoid areas that get pinched by your belt.

And if your site gets red, swollen, or starts leaking? Change it. Now. Don’t wait. A blocked or dislodged cannula can mean no insulin for hours. And that’s how diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) starts. One Reddit user described waking up with a blood sugar of 28 mmol/L after his tubing came loose overnight. He didn’t notice. He didn’t feel sick until it was too late. DKA can hit in 2-4 hours if the pump stops working. Always carry backup supplies: extra sets, insulin, syringes, glucose tabs.

Safety First: When Things Go Wrong

Here’s the hard truth: your pump doesn’t know when you’re unconscious. If you pass out from low blood sugar, the pump keeps delivering insulin. That’s not a glitch. That’s how it’s designed. So you have to be your own safety net.

If you have a low blood sugar that won’t fix with glucose, remove the pump. Stop the insulin. Treat the low. Call for help. Don’t wait. The ABCD Clinical Guidelines say: if hypoglycemia is persistent, disconnect the pump immediately. Same goes if you’re sick, vomiting, or can’t eat. Your body doesn’t need insulin the same way when you’re not eating. Reduce your basal rate by 20-50%. Talk to your diabetes team before you get sick. Have a plan.

Surgery? If it’s minor and you’ll eat in a few hours, you might keep the pump on-if your site is accessible, your batteries are fresh, and your sugar is between 4-12 mmol/L. If it’s major? You’re switching to IV insulin. Period. Don’t guess. Ask your hospital’s diabetes team. Most don’t know how to manage pumps. Don’t assume they do.

Postpartum? If you’re breastfeeding, your insulin needs drop by 10-20% or more. Your body’s changing. Your pump settings must change too. Same for puberty, illness, or starting a new job. Life moves. Your pump must move with it.

Training and Real-World Challenges

Most clinics push you into pump therapy after a 2-hour demo. That’s not enough. The American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists recommends at least 15 hours of structured training. That means: how to insert a set, how to troubleshoot occlusions, how to calculate boluses, how to respond to alarms, how to handle low and high blood sugar without panic.

And it’s not just technical. It’s psychological. 45% of users report pump failure within the first year. 32% get skin reactions. 38% of high blood sugars come from miscounting carbs. You have to be good at math. You have to be consistent. You have to be honest with yourself.

One user on Insulin Pumpers said: "I thought the pump would make life easier. It did-but only after I learned to treat it like a co-pilot, not a babysitter." That’s the key. It’s a tool. It doesn’t replace your brain. It enhances it.

What’s New in 2025

The Tandem Mobi, released in 2023, is the smallest pump on the market-small enough for kids. It’s simple, loud alarms, and a screen you can read with gloves on. The Omnipod 5 works with any CGM now, not just one brand. That’s a big deal. No more being locked into one system.

Next up? Pumps that deliver both insulin and glucagon. Glucagon raises blood sugar. So if your sugar drops too low, the pump can give a tiny shot to bring it back. It’s like having a second pancreas. But it’s still in trials. Not yet approved. And it’s expensive.

Cost is still a barrier. In the U.S., pumps and supplies run $6,500-$8,200 a year. In the UK, access is better through the NHS, but delays are common. If you’re waiting, ask about loaner pumps. Don’t go without.

Final Thought: It’s Not About the Machine

The best pump in the world won’t fix bad habits. If you skip checks, ignore highs, never test your basal, you’re not using the pump-you’re gambling with it. The people who succeed? They track everything. They adjust constantly. They call their team when something’s off. They carry backup. They know their numbers. They don’t wait for alarms to scream before they act.

CSII gives you freedom. But freedom comes with responsibility. And responsibility means showing up-even on the days you don’t feel like it. Because when your pump fails, you’re the only one who can fix it.

How often should I change my insulin pump infusion set?

Change your infusion set every 2-3 days. Leaving it in longer increases the risk of infection, blocked cannulas, and poor insulin absorption. Skin irritation and lipohypertrophy are common after 4 days. Always rotate sites-abdomen, thighs, and upper arms are best. Never reuse a site within 3 weeks.

What’s the difference between basal rate and bolus?

The basal rate is the small, continuous trickle of insulin your pump delivers 24/7 to manage your background insulin needs-like keeping your blood sugar steady between meals and overnight. A bolus is a larger, on-demand dose you give yourself to cover carbs in food or to correct high blood sugar. Basal is automatic. Bolus is manual-and you control when and how much.

Can I use an insulin pump if I have type 2 diabetes?

Yes, if you require intensive insulin management and your diabetes is unstable. The American Diabetes Association includes insulin pump therapy as an option for type 2 diabetes patients who need multiple daily injections and struggle with blood sugar control. It’s not first-line, but it’s effective for those with high insulin needs, erratic eating patterns, or frequent highs and lows.

What should I do if my pump stops working?

If your pump stops, switch to insulin injections immediately. Use your long-acting insulin (like Lantus or Levemir) for basal coverage and rapid-acting insulin (like Humalog) for meals and corrections. Calculate your doses based on your usual total daily dose. Check your blood sugar every 2 hours. Call your diabetes team. Never go more than 2-3 hours without insulin. Keep backup insulin and syringes with you at all times.

Is it safe to sleep with an insulin pump?

Yes, it’s safe to sleep with an insulin pump. Most people clip it to their pajamas, tuck it under their pillow, or use a pump holster. The key is ensuring the tubing isn’t kinked or compressed. If you roll onto the site, it might block the flow. Use alarms to alert you to high or low blood sugar overnight. Some pumps have automatic low glucose suspend features that pause insulin delivery if your sugar drops too low-this adds a layer of safety while you sleep.

Why do I keep getting high blood sugar after meals even with a bolus?

This usually means your insulin-to-carb ratio is too high (you’re giving too little insulin), your bolus timing is off, or the food digests slowly. High-fat meals (pizza, pasta with cream sauce) delay carb absorption. Use an extended or dual-wave bolus for these. Also, check your infusion site-is it blocked or old? Did you forget to account for insulin on board (IOB)? Always use your pump’s bolus calculator with IOB enabled. And test your ICR every few months by fasting and eating a known carb meal.

Next steps: If you’re new to CSII, schedule a pump training session with a certified diabetes educator. Bring your logbook or app data. Ask for a basal test protocol. Practice bolusing for different meals. Keep backup supplies in your bag, car, and work drawer. And remember-your pump is only as smart as the person using it.

Brian Bell

November 14, 2025 AT 04:13Ashley Durance

November 15, 2025 AT 01:10Ryan Anderson

November 16, 2025 AT 06:25gent wood

November 17, 2025 AT 20:36Hrudananda Rath

November 19, 2025 AT 04:48Jane Johnson

November 21, 2025 AT 02:33Brian Bell

November 22, 2025 AT 14:03Eleanora Keene

November 23, 2025 AT 09:29Scott Saleska

November 23, 2025 AT 09:51Don Ablett

November 25, 2025 AT 00:28Dilip Patel

November 26, 2025 AT 00:33Nathan Hsu

November 27, 2025 AT 09:50