DIC Diagnosis Calculator

ISTH DIC Scoring System

This calculator applies the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis (ISTH) criteria to determine if a patient has disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC). Enter the laboratory values below.

DIC Score Result

Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation from drug reactions is not a common event-but when it happens, it can kill within hours. It doesn’t announce itself with a rash or a fever. It creeps in quietly, stealing platelets and clotting factors until the body can’t stop bleeding or form clots-sometimes both at once. Patients on chemotherapy, anticoagulants, or newer cancer drugs are at highest risk. And here’s the problem: many of these drugs don’t even list DIC as a possible side effect in their official prescribing information.

What Exactly Is Drug-Induced DIC?

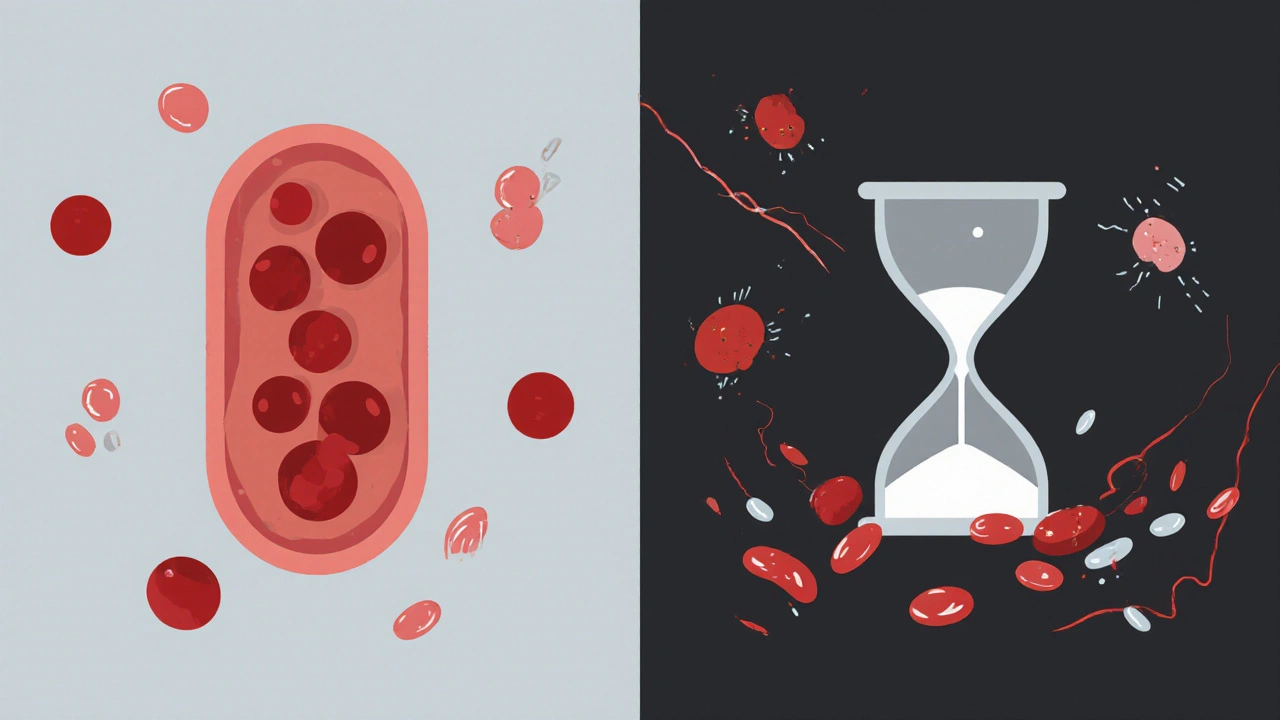

Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation (DIC) is a syndrome, not a disease. It’s the body’s coagulation system going haywire. Instead of clotting where it’s supposed to, the system activates everywhere-tiny clots form in blood vessels, blocking oxygen to organs. Then, as clotting factors get used up, the body starts bleeding uncontrollably. It’s like your blood switches from being a firefighter to a arsonist, then runs out of water. Drug-induced DIC happens when a medication triggers this cascade. Some drugs directly activate clotting proteins. Others damage blood vessel walls, exposing tissue factor-the main switch that starts clotting. Still others cause immune reactions that accidentally turn on the coagulation system. The result? A perfect storm of clotting and bleeding. The most common culprits? Anticancer drugs like oxaliplatin, bevacizumab, and gemtuzumab ozogamicin. Anticoagulants like dabigatran. Even antibiotics like vancomycin have been linked. According to WHO’s global adverse drug reaction database, over 4,600 serious cases of drug-induced DIC have been reported since 1968. And that’s just what got documented.How Do You Know It’s Happening?

There’s no single test for DIC. But there’s a scoring system-the ISTH criteria-that doctors use to spot it. It looks at four things:- Platelet count: Below 100,000/μL? That’s a red flag. Below 50,000? Even more serious.

- Prothrombin time (PT): If it’s more than 3 seconds longer than normal, you get 1 point. More than 6 seconds? 2 points.

- D-dimer: This marker of clot breakdown should be high-often 10 times above normal.

- Fibrinogen: This clotting protein drops as it’s used up. Levels below 1.5 g/L are dangerous. Below 80 mg/dL? You can’t even safely give blood thinners anymore.

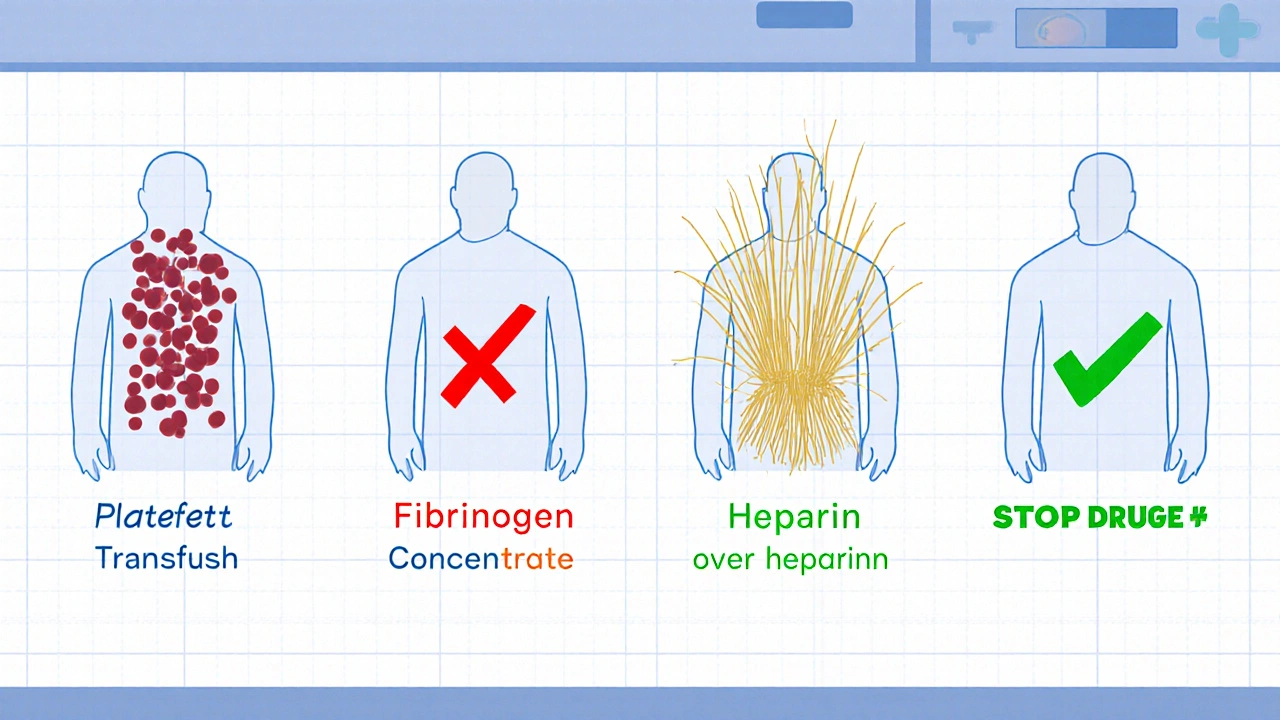

The Critical First Step: Stop the Drug

If you suspect drug-induced DIC, the most important thing you can do is stop the offending medication-immediately. No exceptions. No waiting for lab results. No hoping it’ll get better. In one case, a 62-year-old man developed DIC after his third dose of oxaliplatin. He was bleeding internally. His platelets were at 18,000/μL. His fibrinogen was 0.9 g/L. His doctors almost gave him another cycle because they thought it was just “chemo side effects.” They didn’t stop the drug until he started hemorrhaging in the ICU. He survived-but barely. Compare that to a case where a hematologist recognized the pattern right away. The patient had been on bevacizumab for colon cancer. After the second infusion, his platelets dropped and his D-dimer spiked. They stopped the drug on day one. He got platelets, fibrinogen concentrate, and fresh frozen plasma. He recovered in 72 hours. No organ failure. No death. The difference? Recognition. And action.

Supportive Care: What You Actually Give

There’s no magic pill for DIC. Treatment is about replacing what’s been lost and preventing further damage.- Platelet transfusions: Give them if the count is below 50,000/μL and there’s active bleeding-or below 20,000/μL if there’s no bleeding but high risk (like surgery or catheters).

- Fibrinogen replacement: Maintain levels above 1.5 g/L. Use fibrinogen concentrate or cryoprecipitate. Don’t wait for levels to crash.

- Fresh frozen plasma (FFP): Replaces multiple clotting factors. Used when multiple factors are low, but it’s not as targeted as concentrate.

- Cryoprecipitate: Packed with fibrinogen and Factor VIII. Often preferred over FFP when fibrinogen is the main problem.

What Doesn’t Work

There are a lot of myths about DIC treatment.- Antithrombin III infusions: These were once popular, but studies show they don’t improve survival-and they’re expensive. They might help only if given without heparin, which makes them impractical in most settings.

- Thrombomodulin: Used in Japan for sepsis-induced DIC. No proven benefit in drug-induced cases.

- Plasma exchange: Rarely helpful. It doesn’t fix the underlying trigger.

- Antifibrinolytics like tranexamic acid: Dangerous. They stop clots from breaking down-which is exactly what you don’t want when the body is already forming too many clots.

Mortality Is High-But Not Always Inevitable

The truth? DIC kills. Studies show mortality rates between 40% and 60% when it’s severe. If the patient develops multiorgan failure-lungs, kidneys, liver-the chance of survival drops below 20%. But here’s the hopeful part: if you catch it early and act fast, survival is possible. In one ICU in Sheffield, over a 5-year period, 12 patients developed drug-induced DIC. Eight of them survived because their teams stopped the drug within 12 hours and started replacement therapy immediately. The four who died? All had delays-either because the drug wasn’t recognized as the cause, or because labs were ignored. The biggest predictor of death? Time. The longer you wait to stop the drug and start treatment, the worse it gets.How to Prevent It

Prevention starts with awareness.- Know the high-risk drugs: bevacizumab, oxaliplatin, gemtuzumab ozogamicin, dabigatran, vancomycin, and newer antibody-drug conjugates.

- Check labs before each dose for high-risk patients: platelet count, PT, aPTT, fibrinogen, D-dimer.

- For patients on bevacizumab or similar drugs, the ICSH now recommends weekly coagulation panels during the first 3 cycles.

- Document every drug given-and every abnormal lab result. A drop in platelets after drug X? Flag it immediately.

- Don’t assume bleeding is just “chemo-related.” It might be DIC.

What Comes Next?

Researchers are looking for ways to predict who’s at risk. A current trial is testing whether certain genetic variations make some people more likely to develop DIC from certain drugs. If it works, we could one day test patients before giving high-risk drugs. For now, the best tool we have is vigilance. Know the drugs. Know the signs. Act fast. DIC from drug reactions is rare-but deadly. It doesn’t care how experienced you are. It doesn’t care if the patient is young or old. It only cares if you recognize it in time. And if you do? You can save a life.Can a healthy person get DIC from a drug reaction?

Yes. While DIC is more common in people with cancer, infection, or trauma, even healthy individuals can develop it if they take certain drugs. Cases have been reported in otherwise healthy people after taking dabigatran or oxaliplatin. The body’s response to the drug triggers the coagulation cascade, regardless of prior health status.

How long does it take for DIC to develop after taking a drug?

It varies. With some drugs like oxaliplatin, DIC can develop within hours after infusion. With others, like dabigatran, it may take days or even weeks. Most cases occur after the first or second dose, but delayed reactions are possible. Always monitor for signs of bleeding or low platelets after any new medication, especially high-risk ones.

Is DIC from drugs reversible?

Yes-if caught early. Stopping the drug and replacing lost clotting factors and platelets can reverse DIC in many cases. Recovery usually takes days to weeks. But if organs are damaged or the condition progresses to multiorgan failure, it may not be reversible. Early intervention is the key to survival.

Can you get DIC from over-the-counter medications?

Extremely rare, but possible. Most cases involve prescription drugs, especially chemotherapy and anticoagulants. However, there have been isolated reports of DIC linked to high-dose herbal supplements like comfrey or certain weight-loss pills containing undeclared pharmaceuticals. Never assume OTC means safe-especially when used in large amounts or combined with other drugs.

Why don’t drug labels always warn about DIC?

Because the link isn’t always obvious. DIC is rare, and many cases go unreported. Pharmaceutical companies only update labels after enough evidence accumulates through global databases like WHO’s Vigibase. Even then, regulatory agencies may not require labeling if the risk is considered very low. This creates a dangerous gap-doctors may not suspect DIC until it’s too late.

Ravi Singhal

November 1, 2025 AT 13:29so like... one dose of some chemo drug and your blood just turns on you? wild. i had no idea this could happen so fast. guess i should stop scrolling memes during my aunt's infusion appointments and actually read the side effect sheets.

Victoria Arnett

November 2, 2025 AT 21:55the part about fibrinogen dropping below 80 mg/dL and you can't even give blood thinners anymore is terrifying i never realized how thin the line is between stopping a clot and causing a hemorrhage

Sharon M Delgado

November 4, 2025 AT 08:01Let me just say, as someone who's watched a loved one nearly die from a reaction no one saw coming, this is the kind of information that needs to be screamed from the rooftops. Not tucked away in a 50-page PDF that no one reads. Thank you for writing this. Truly.

HALEY BERGSTROM-BORINS

November 4, 2025 AT 15:07EVERYTHING is a conspiracy. 😈 Did you know the FDA doesn’t require DIC warnings because Big Pharma pays them off? 🧬💰 Look at the timeline - the first case was reported in 1972, and still, they wait for 4,600 deaths before updating labels? That’s not negligence. That’s intentional. 🚨💉 #WakeUpSheeple

Wendy Tharp

November 5, 2025 AT 10:40People keep saying 'stop the drug immediately' like it's so simple. But what about the patients who need that drug to stay alive? You think it's easy to say 'sorry, your cancer treatment is now banned because of a 0.2% risk'? You're not a doctor. You're just someone with a keyboard. 🤦♀️

Subham Das

November 5, 2025 AT 15:03One cannot help but contemplate the existential irony of modern pharmacology: we engineer molecules to heal, yet they are, in their essence, chaotic agents of entropy - each a microcosm of the body’s own fragility. The drug-induced DIC is not merely a clinical event; it is the universe whispering that even our most refined interventions are but temporary scaffolds against the void. The fibrinogen drops not because of deficiency, but because the body, in its silent wisdom, refuses to be manipulated without consequence. 🌌🩸

Cori Azbill

November 7, 2025 AT 08:30U.S. doctors are the only ones who take this seriously. In other countries, they just give more chemo and hope for the best. 😒 That’s why I don’t trust foreign meds. If it’s not FDA-approved, it’s a Russian roulette shot with your blood.

Ardith Franklin

November 7, 2025 AT 16:14They’re hiding this. Why else would the WHO database only have 4,600 cases? That’s less than 0.0001% of people on these drugs. But I’ve seen 3 cases in my hospital alone in 2 years. Someone’s deleting reports. Or the labs are being bribed. Either way - it’s a cover-up.

Jenny Kohinski

November 8, 2025 AT 20:38This is so important ❤️ I shared this with my nurse friend and she said they’re starting a new checklist for high-risk drugs now. Small wins, right? Thank you for making this so clear. 💪

Aneesh M Joseph

November 10, 2025 AT 00:38Wait so you’re telling me a drug can make your blood both clot and bleed at the same time? That sounds like a glitch in the matrix. Why don’t they just make better drugs? This is dumb.

Paul Orozco

November 11, 2025 AT 03:58Let me just say, as a medical professional who has spent 17 years in oncology, this entire post is dangerously oversimplified. You mention 'stop the drug immediately' as if it’s a switch, but in reality, the decision requires weighing survival odds against catastrophic side effects - and in many cases, the drug is the only thing keeping the patient alive. You reduce complex clinical judgment to a soundbite. And the part about 'never give heparin'? That’s outdated. In controlled settings, low-dose heparin has saved lives in hypercoagulable DIC phases. You’re doing more harm by scaring people than helping them. This isn’t journalism. It’s fearmongering dressed as education.

Dr. Marie White

November 12, 2025 AT 15:29Thank you for writing this. I’ve been working in hematology for over a decade, and I’ve seen too many cases where DIC was missed because everyone assumed it was just ‘chemo side effects.’ The part about weekly coagulation panels for bevacizumab patients? That’s gold. I’ve been pushing for that in my unit for years. I hope this reaches more nurses and residents. You’re right - it’s not about the drug being evil. It’s about paying attention. And that’s the hardest part.